Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS or altitude sickness) and its more severe forms such as High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) and High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) are very real problems when trekking at high altitude.

This article will give an in-depth guide on high altitude acclimatization, the effects of altitude sickness and how best to deal with the problem. The article will also discuss preventative altitude sickness medication.

Disclaimer: Whilst the information we provide is as reliable as possible, we are not medical experts and would recommend seeking the advice of a qualified doctor if you feel you have any medical issues that might be exasperated by high altitude. This article is written as an information resource only and shouldn't to be relied upon for any medical diagnostics or treatment.

Please note that the information we have gathered here has been taken from our own personal experience, talking with like-minded trekkers, NHS, Rick Curtis' 'Outdoor Action Guide to High Altitude' and recent research from the medical clinic at Everest Base Camp. However, research is progressing extremely fast in this area and, therefore, any information we provide may be out of date. It is your responsibility to research the latest information for yourself so that your are prepared for high altitude acclimatization.

High altitude acclimatization - Introduction

High altitude acclimatization is the process in which our body becomes accustomed to lower levels of oxygen in the surrounding air. This process can only take place gradually as you move up through various levels of altitude, spending time at each level before progressing upwards.

Air Density, Oxygen and Altitude

To fully understand high altitude acclimatization you need to be aware of the relationship your body has between the altitude you're at, the air density and the level of oxygen available to you.

Standing at sea level oxygen makes up around 21% of the air and the barometric pressure is roughly 760 mmHg (millilitres of mercury). As you ascend higher in altitude the oxygen levels actually stay very similar (until about 69,000 feet), however, the air density greatly decreases. This means that the air density packing all the oxygen molecules tightly together becomes thinner which allows the oxygen molecules to spread over a greater distance. There is still the same amount of oxygen in the air but as you get higher up it spreads out because there is less pressure.

At 3,600 metres (12,00 feet) the barometric pressure in the atmosphere is roughly 480 mmHg - far lower than the sea level pressure. This means that with the air being thinner and the oxygen spreading out you have far less available oxygen per breath.

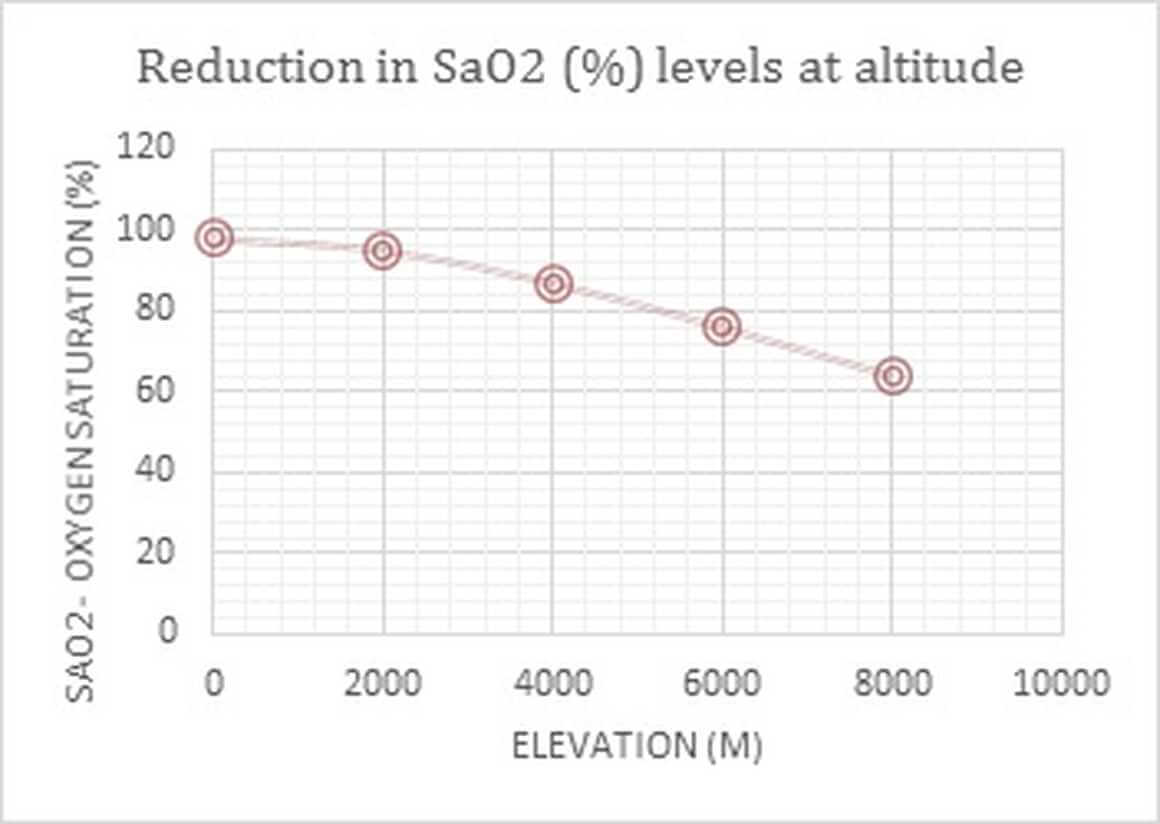

Blood oxygen saturation

Your body deals with the decreased oxygen by breathing faster and more deeply, even when your resting, so that your body gets the necessary oxygen levels into your bloodstream. This is more commonly known as blood oxygen saturation (SO2).

The chart provided below demonstrates a typical blood oxygen saturation profile as one ascends to higher levels of altitude. As can be seen, at 6,000 metres your body's blood oxygen saturation level is down almost 20%!

As experienced high altitude trekkers will tell you, there are three levels of altitude. The first is 'high altitude' (2,500 - 3,500 metres), the second is 'very high altitude' (3,500 - 5,500 metres) and lastly, 'extreme altitude' (above 5,500 metres).

Most people can ascend to anywhere below 2,500 metres without experiencing any negative effects of altitude. However, above this threshold your body's physiology starts to react to changes in oxygen levels and air density.

Predicting how you will react to altitude is very difficult as previous research has found no correlation between age, gender, fitness levels etc. However, major causes of AMS are ascending too quickly without acclimatizing gradually, exerting yourself too hard physically at altitude and not staying hydrated enough.

To properly acclimatize you need to take all these factors in to account and make sure you ascend gradually, stay well hydrated and don't overdo yourself physically.

Climbers have a term called the acclimatization line which illustrates this point further.

Acclimatization line

The acclimatization line is the point at which a person demonstrates symptoms of altitude sickness. An example would be that if your acclimatization line is at 3,000 metres, you would need to spend a day or two at that altitude level to give your body time to acclimatize to the height. After several days your body would have acclimatized and your new acclimatization line might be 3,750 metres. This means that you can ascend to 3,700 metres without AMS symptoms, however, if you ascended to 4,000 metres you would then experience AMS.

When trekking at altitude you need to find your acclimatization line at each stage of your climb and allow your body time to acclimatize to the new altitude. If you ascend through your acclimatization line then you are almost guaranteed to get AMS and, instead of acclimatizing, your symptoms will only worsen. It is therefore critical that you stay below your acclimatization line to see any improvement.

This is why it is imperative that you do not continue to ascend higher if you have any AMS symptoms.

Higher altitude - How the body adapts

The good news is regardless of who you are, your body will be able to adapt given enough time. Your body will adapt in four ways that are worth mentioning here:

1. Your body will adapt by breathing faster and more deeply

2. Your body will increase its red blood cell count, allowing your blood to carry higher amounts of oxygen

3. Your body increases pressure to your Pulmonary Capillaries which forces blood into parts of your lungs not used when breathing at sea level

4. Your body produces a particular enzyme in greater quantity that causes oxygen to be released from hemoglobin to the blood tissue

These four points demonstrate that your body is certainly able to adapt and cope at altitude - it just needs time.

Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS)

As discussed above, AMS or 'altitude sickness' or 'altitude illness' stems from rising in altitude too fast where the levels of available oxygen are far lower and inhibit normal psychological processes.

On average, people start to feel the altitude at roughly 3,000 metres (10,000 feet), however, some people can experience AMS symptoms as low as 2,400 metres (8,000 feet).

Mountaineers define three distinct levels of AMS - mild, moderate and serious, all of which we now discuss.

Mild symptoms

Mild symptoms include:

- Headaches

- Fatigue

- Nausea and Sickness

- Loss of appetite

- Shortness of breath

- Disturbed sleep

If you feel the onset of any of these symptoms you need to make sure you communicate them to your guides and fellow trekkers. Mild symptoms will generally clear when you spend a day at the altitude level they began to appear. This is why ascending slowly is so important.

Moderate symptoms

Moderate symptoms include:

- Severe nausea - often vomiting as a result

- Severe headaches that will not dissipate with medication

- A decrease in your coordination (known as Ataxia)

- Feeling very weak and fatigued

- Shortness of breath

The simple way to tell if your symptoms are moderate is when your mild symptoms worsens to the point where it is debilitating. The most common is a decrease in your coordination levels and severe nausea that often results in vomiting.

Continuing to ascend with these symptoms is possible, although extremely dangerous, and will certainly lead to your symptoms developing further which will stop you from being able to continue.

Please note that continuing to ascend with moderate symptoms can lead to death.

If moderate symptoms present themselves it is critical that you descend at least 300 metres (1,000 feet) and wait until your symptoms have cleared. The longer you give your body the better and the more likelihood you will have of symptoms staying away as you ascend again.

Serious or severe symptoms

Severe symptoms include:

- Shortness of breath during rest periods

- Mental capacity decreases - hallucinations

- An inability to walk

- Your lungs experience fluid build up

Obviously to ascend when experiencing any of these conditions is critically dangerous and should never happen. People with severe AMS symptoms are usually struggling for breath, unable to think straight and cannot walk.

The two most notable conditions associated with severe AMS are High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) and High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE). HAPE occurs when fluid leaks into your lungs through the capillary wall and HACE occurs when fluid seeps into your brain.

Both conditions are extremely dangerous and usually occur from ascending too quickly or spending too long at high altitude.

Below we will discuss both.

High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE)

High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE), is a common condition associated with AMS. Fluid builds up in your cranium and forces your brain tissue to swell. HACE is extremely dangerous and life threatening.

If you think you are experiencing HACE you should descend the mountain as quickly as possible and seek medical support.

Things to look out for when identifying HACE.

- Hallucinations

- Disorientation

- Memory loss

- Coma

- Severe headaches that persist even when medication is taken

- Loss of coordination (Ataxia)

Generally HACE symptoms will come in the night. It is vital you do not wait until morning to seek assistance, start descending immediately (even if dark) and seek medical support as early as possible. By staying at altitude with HACE you are increasing the likelihood of fatality. Do not ascend under any circumstances. If you have oxygen this can be administrated to the person as you rapidly descend, as can the drug Dexamethasone (this is a prescription drug with many side affects - for this reason we do not carry this drug on our tours).

High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE)

High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) is a common condition associated with AMS and is caused by a build up of fluid in the lungs.

The build up of fluid in the lungs serves to prevent effective oxygen exchange and, therefore, decreases the level of oxygen entering your bloodstream.

Like HACE, HAPE occurs most frequently from ascending too high too fast. It is also a life threatening condition.

Symptoms to look for when identifying HAPE.

- Very tight chest

- Extreme shortness of breath even when resting

- The feeling of suffocating - especially when sleeping

- Extreme weakness and fatigue

- Hallucinations, irrational behaviour and confusion

- A cough that brings up a white, frothy fluid

If the person suffering starts to act irrationally, sees hallucinations or is in a generally confused state, then it is clear that the condition has started to effect the brain due to lack of oxygen in the bloodstream.

If there is any available oxygen then it should be administered straight away. The drug Nifedipine has been demonstrated to alleviate the condition somewhat, however, a rapid descent is the only cure. Please note: Nifedipine is a prescription drug with many side affects - for this reason we do not carry this drug on our tours.

Make sure when descending that the person suffering with HAPE does not exert themselves as this can worsen the situation. A stretcher or helicopter evacuation is the best option usually as it's the easiest option for the person in question.

Once at the bottom seek medical support immediately.

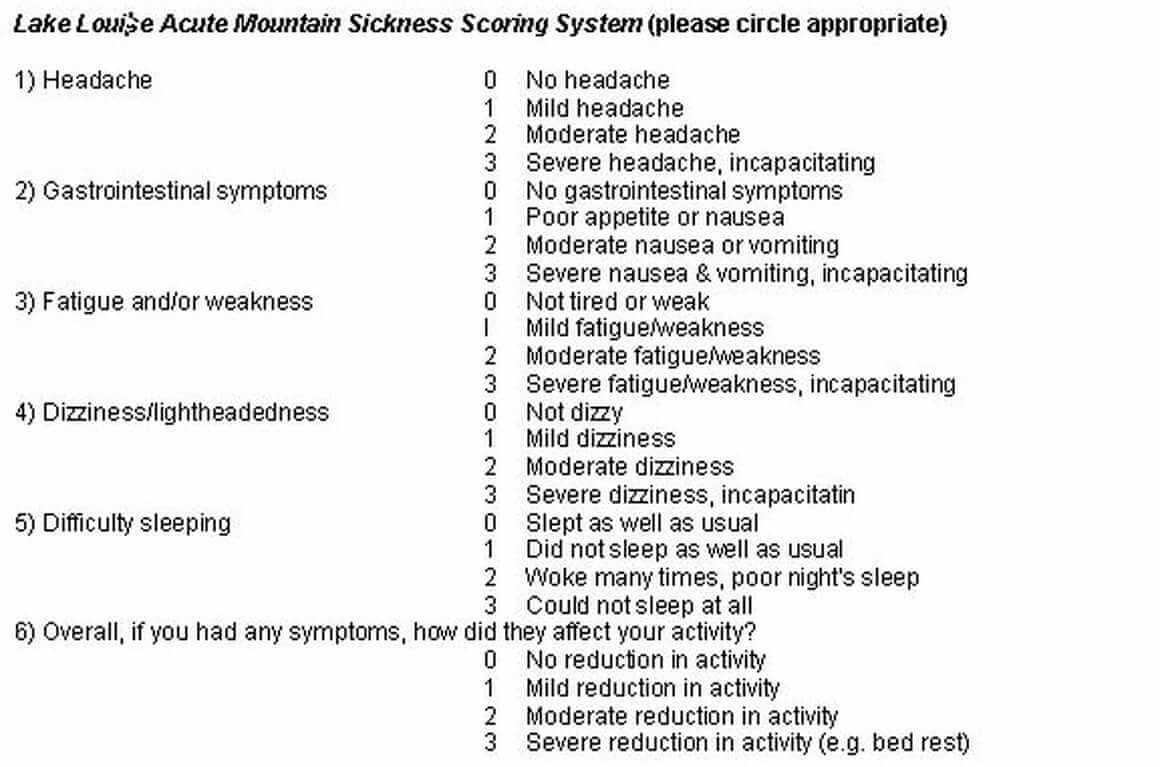

Lake Louise altitude sickness scorecard

Whilst there are a number of ways to gauge altitude sickness, the most common method is using the Lake Louise altitude sickness scorecard as seen below.

Scoring between 3 and 7 is a sign of mild to moderate altitude sickness. Scoring above 7 is a sign of severe altitude sickness.

Ideally you should keep a scorecard handy at all times and take pulse readings and spot oximeter readings to monitor yourself throughout your climb.

If your scorecard reaches 8 or your SO2 reading is below 75% you should abandon any trek or climb and descend rapidly.

On all of our treks and climbs our guides will take your Lake Louise score each day, along with measuring your pulse and SO2 scores.

Golden rules

Trekking to high altitudes does not have to be dangerous, it simply needs to be well planned. Following some basic rules will help with preparation.

In particular:

- Start small and work your way up. Try not to climb to high altitudes without first trekking some smaller routes to acclimatize.

- If you are a novice high altitude trekker then make sure your you do not rush. The longer it takes to reach the summit, or high point of your trek, the more time your body has to acclimatize.

- Ideally your route should allow you to climb high and sleep low. This is important as spending extended periods of time at high altitude is not safe.

- Do not over exert yourself. Keep yourself at a pace that suits you. This is key at high altitude where there is less oxygen.

- Keep well hydrated. Dehydration will only exacerbate any problems and make your trek a lot less fun.

- Don't drink alcohol or take stimulants, caffeine, smoke etc.

- We would recommend that you take acetazolamide (Diamox)

As the charity altitude.org recommend, there are three golden rules in identifying altitude sickness:

- If you feel at all unwell on your trek then you must assume you have altitude sickness until proven otherwise.

- If you have any symptoms of altitude sickness do not ascend any further.

- If your symptoms develop further then descend immediately.

Preventative Medications (Diamox)

Acetazolamide (Diamox) is a drug that has been proven to help in preventing altitude sickness.

The drug works by increasing the acidity in your blood which acts as a diuretic and forces you to urinate more frequently. Your body equates high acidity levels with increased CO2 in the blood and, therefore, forces you start breathing faster and deeper to lose the CO2. The drug is essentially tricking your body into breathing faster and deeper which greatly increases the level of oxygen in your blood that helps prevent the onset of altitude sickness.

Please note that Diamox is simply a preventative drug and does not cure altitude sickness or prevent it entirely, it simply can help. If altitude sickness symptoms appear then descending is the only cure. Diamox should never be taken to continue upwards with AMS symptoms.

Remember, Diamox is a prescriptive medicine and you will need to consult your doctor if you are thinking of taking it. The drug is not suitable for people with liver or kidney issues and should not be taken by pregnant woman.

We would recommend taking Diamox for a couple of day roughly two weeks prior to your trek to see if you experience any side effects.

Some typical side effects associated with Diamox are:

- Frequent urination. Every person taking Diamox will experience this so it is important that you drink loads to combat this. If you don't keep hydrated you run the risk of developing kidney stones.

- Feeling of tingling or numbness in the finger tips. Many people experience this and, whilst it can be worrying, it is not harmful.

- Alteration in your taste buds - some food may taste differently.

- Vomiting, diarrhoea and nausea. These symptoms are not common and should be identified during your pre-testing. Unfortunately these symptoms are common signs of AMS and can be misdiagnosed.

- Confusion or drowsiness. Once again this can be confused with AMS and should be tested before departing.

Diamox usually comes in 250mg tablets and we recommend taking half a tablet in the morning and half in the evening. We recommend starting one day before your trek begins and continually taking it until you start to descend. There is no need to take Diamox when descending.

Trekking insurance

As discussed above, the risks of high altitude trekking are considerable and should be attempted with great care. We strongly recommend taking out trekking insurance cover. Check out our article on trekking insurance as it provides a comprehensive guide to all your insurance options.